How to Live In The Woods [Complete Guide]

ZacharyWilliamPractical, safety-first advice for anyone considering a season — or a lifestyle — closer to the trees.

Updated: November 2025

Read this as a reality check and a planning guide — not a fantasy. The woods are beautiful, but they are not forgiving.

1. What “Living in the Woods” Really Means

“Living in the woods” can mean completely different things depending on who you ask. Before you buy gear or quit your job, clarify what you actually want:

- Short-term immersion – A 1–4 week trip to reset and learn basic skills.

- Seasonal or part-time living – Splitting your year between a home base and a long-term forest camp or cabin.

- Full-time off-grid lifestyle – A primary residence on private land in or near the woods, with your own water, power and shelter.

Each path has different legal, financial and safety requirements. A realistic approach is to treat full-time forest living as something you graduate into after multiple shorter trips, not something you jump into overnight.

2. Is It Legal to Live in the Woods?

This guide is not legal advice. Rules vary by country, state and even individual forest district. Always confirm with local authorities before setting up long-term camp.

2.1 Public land (National Forests, BLM, State Forests)

In much of the U.S., dispersed camping on public land is allowed — but only for a limited number of days before you must move. For example, many U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management areas limit stays to roughly 14 days within a 28-day period, sometimes less in high-use areas.

That means you typically cannot legally set up a permanent home in a random clearing and stay indefinitely. You are expected to move, rotate areas, and follow all local rules on fires, vehicle use, waste and group size.

2.2 Private land

Long-term living in the woods is most stable and legal when you:

- Own forested land outright, or

- Have written permission (and often a lease) from the landowner.

Even on private land, zoning codes may limit where you can live full-time, what structures count as a legal residence, and how septic/waste must be handled.

2.3 A practical approach

For most people, the safest plan is:

- Use public land for short-term trips to build skills.

- Research and, if possible, purchase or lease land if you want a long-term forest base.

- Talk to local planning departments about building codes, tiny homes, and off-grid cabins.

3. Step 1 – Choose Your Location & Season

Everything about living in the woods — shelter, gear, risks — depends on where and when you go.

3.1 Key questions before you pick a forest

- Climate: Do you understand the winter lows, summer highs, rain and snow patterns?

- Access: Can you get in and out with your vehicle in all seasons?

- Water: Are there reliable streams, springs or lakes — and are they safe to filter?

- Fire risk: Are there seasonal fire bans? Is the area prone to wildfires or evacuation orders?

- Distance to town: Where is the nearest grocery store, clinic, and fuel station?

Start with a forest area you already visit for day hikes or weekend camping. You’ll know the roads, trailheads and rough weather patterns, which removes a lot of guesswork.

3.2 Start with the easiest season

For most U.S. regions, the easiest first season is:

- Late spring through early fall in temperate forests.

Winter living in the woods adds serious risks: hypothermia, deep snow, limited solar power and difficult travel. Treat winter as an advanced level, not your first chapter.

4. Step 2 – Build the Right Skill Set

The woods reward skills more than gear. Even if you plan to bring modern equipment, certain basic skills are non-negotiable.

4.1 Navigation & situational awareness

- Reading topographic maps and using a compass.

- Staying oriented without cell service or a clear trail.

- Understanding how fast terrain and weather can change.

4.2 Fire safety & heat

- Knowing when fires are banned, and respecting that.

- Building small, controlled fires only in safe conditions.

- Using stoves safely inside vestibules or shelters (and when not to).

4.3 Water treatment

- Filtering surface water (pump filters, squeeze filters, gravity bags).

- Disinfecting with boiling or chemical tablets when needed.

- Keeping “dirty” and “clean” containers separate.

4.4 Leave No Trace ethics

Learn and apply the seven Leave No Trace principles: plan ahead, travel and camp on durable surfaces, dispose of waste properly, leave what you find, minimize campfire impacts, respect wildlife, and be considerate of others.

4.5 Medical & emergency basics

- Recognizing hypothermia, heat exhaustion and dehydration.

- Carrying and using a first-aid kit (and taking a wilderness first-aid course if possible).

- Having a written emergency plan and a way to call for help (satellite messenger, PLB, etc.).

5. Step 3 – Core Gear & Supply Checklist

Your exact gear list will depend on climate and how minimalist you want to live, but these categories cover the essentials for medium-term forest living.

- Shelter (tent, tarp, or cabin; plus repair kit)

- Sleep system (sleeping bag rated for your coldest nights, sleeping pad)

- Clothing layers (base, insulation, waterproof shell; extra socks)

- Cooking setup (stove, fuel, lighter, pot, utensils, bear-safe food storage if required)

- Water system (containers, filter, backup purification method)

- Lighting (headlamp, backup light, spare batteries or rechargeable power)

- Tools (knife, small saw, multi-tool, cordage)

- First-aid kit and basic medications

- Navigation (map, compass, GPS/phone with offline maps)

- Power & communication (portable power station, solar, radios, satellite communicator)

5.1 Shelter & sleep

Your shelter should handle the worst likely night, not just the average weather.

- 4-season or sturdy 3-season tent if you expect storms or shoulder-season snow.

- Tarp or secondary shelter for cooking and gear storage.

- Sleeping bag rated at least 10–20°F below your expected nighttime lows.

- Insulated sleeping pad to keep you off cold ground.

5.2 Clothing strategy

Think in layers, not single heavy garments:

- Moisture-wicking base layers.

- Insulating mid-layer (fleece or puffy jacket).

- Waterproof/windproof shell.

- Dedicated sleep clothes and multiple pairs of socks.

5.3 Tools & repair

- Small fixed-blade knife or quality folding knife.

- Compact saw for dead and down wood where permitted.

- Duct tape, repair patches for tent and sleeping pad, spare cordage.

5.4 Example gear overview table

| Category | Examples | Tips for Woods Living |

|---|---|---|

| Shelter | Freestanding tent, tarp shelter, small off-grid cabin | Favor proven, storm-worthy designs over ultralight experiments for long stays. |

| Sleep system | Down or synthetic bag, insulated pad, liner | Err on the warm side; sleeping cold every night will burn you out fast. |

| Cooking | Canister stove, liquid fuel stove, fire grill where legal | Bring at least one stove that works well in your coldest expected temps. |

| Water | 2–4 bottles, gravity filter, backup purification tablets | Plan to carry more than you think you need until you know local sources well. |

| Lighting | Headlamp, small lantern, spare or rechargeable batteries | Hands-free lighting dramatically improves safety around camp at night. |

| Power | Portable power station, solar panel, car charging | Helps you keep phones, radios, headlamps, and work devices alive for weeks. |

6. Water, Food & Cooking in the Woods

6.1 Water: your first priority

Plan for at least 3–4 liters per person per day between drinking, cooking and basic hygiene. In hot weather or heavy work, you may need more.

- Scout reliable sources ahead of time on maps and satellite imagery.

- Carry enough storage to bridge dry sections (jugs, collapsible bladders, bottles).

- Always treat surface water — even cold, clear streams.

6.2 Food for long stays

For multi-week trips, focus on calorie-dense, shelf-stable foods:

- Oats, rice, pasta, dehydrated meals, instant potatoes.

- Beans, lentils, tuna, chicken in pouches or cans.

- Nuts, trail mix, nut butters, energy bars.

- Cooking oils and seasonings to keep meals appealing.

Store food securely in bear canisters, bear-proof boxes, or hung well away from camp where required by local regulations.

6.3 Cooking safety

- Cook away from your sleeping area where wildlife is a concern.

- Never cook in a fully closed tent; carbon monoxide is deadly.

- Know and follow all fire bans and stove restrictions.

7. Hygiene, Waste & Health

Long-term comfort in the woods depends heavily on how you manage hygiene and waste.

7.1 Human waste

- Follow local rules: some areas require you to pack everything out.

- Where allowed, use catholes 6–8 inches deep at least 200 feet away from water, trails and camp.

- Pack out toilet paper in sealable bags where required or recommended.

7.2 Trash management

Pack out all trash — including food scraps and micro-trash like tea bag tags or candy wrappers. Leaving trash invites animals and can get entire areas restricted or closed.

7.3 Staying healthy over weeks or months

- Wash hands regularly, especially before eating or cooking.

- Rotate footwear and dry socks daily to avoid blisters and fungal infections.

- Have a realistic plan for prescription meds and any ongoing medical needs.

- Pay attention to mental health: isolation and long bad-weather stretches are surprisingly hard.

8. Weather, Wildlife & Safety Risks

8.1 Weather and exposure

Most serious backcountry incidents are not from wild animals — they’re from exposure (getting too cold, too hot, or too dehydrated). To reduce risk:

- Check multi-day forecasts before every resupply run.

- Have a conservative “bail-out plan” if a major storm or heat wave is coming.

- Make sure someone in town knows where you are and when you plan to check in.

8.2 Wildlife

- Store food properly to avoid attracting bears and smaller animals.

- Never feed wildlife; it’s dangerous for you and them.

- Know how to react to local species (bears, cougars, snakes, ticks, etc.).

8.3 Fire, smoke & evacuation

In many regions, wildfire risk is now a yearly reality. Stay alert for:

- Fire danger ratings and burn bans.

- Visible smoke columns or ash fall.

- Official alerts on a weather radio, phone (when in service), or via a satellite communicator.

If authorities ask you to evacuate, leave — even if you feel safe. Fires and floods can move much faster than they appear.

9. Power, Lighting & Communication Off-Grid

Even if you love the idea of unplugging, most people still want some electricity in the woods — for lighting, navigation, work devices, or medical equipment. A small, quiet power system lets you stay out longer without relying on noisy generators.

9.1 Why a portable power station helps in the woods

- Recharges phones, radios, satellite messengers and GPS devices.

- Keeps headlamps, lanterns and camera batteries topped up without carrying piles of disposable batteries.

- Lets you run small fans, laptops, or a low-power fridge at a semi-permanent base camp.

9.2 Right-sizing your power for forest living

As a general rule of thumb:

- Under 300Wh: Best for phones, small cameras, headlamps and ultralight setups.

- 300–700Wh: Good for weekend trips with more lights, camera gear and occasional laptop use.

- 700–1,200Wh+: Better for semi-permanent forest camps, off-grid cabins and small fridges.

9.3 Example UDPOWER setups for the woods

To make this practical, here’s how some UDPOWER LiFePO₄ portable power stations map to real “live in the woods” scenarios. Specs below are taken from official UDPOWER product pages.

| UDPOWER Model | Key Specs | Good For |

|---|---|---|

|

|

192Wh capacity, 200W pure sine wave output, about 5.4 lbs, LiFePO₄ battery rated for thousands of cycles. | Minimalist living where you mainly need phone, headlamp and small device charging. Great as a backup bank at a larger camp. |

|

|

256Wh capacity, 400W output, roughly 6.9 lbs, 1.5-hour fast charging, LiFePO₄ cell chemistry designed for 4,000+ cycles. | Long weekends or photography trips where you’re running multiple lights, cameras and charging a laptop or tablet at night. |

|

|

596Wh capacity, 600W rated output (up to 1,200W max), about 12.3 lbs, LiFePO₄ battery and multiple AC, DC and USB ports. | Semi-permanent forest base camp with lights, a low-draw 12V fridge, tool charging, and daily phone or laptop use. |

|

|

1,190Wh LiFePO₄ battery rated for 4,000+ cycles, about 26 lbs, 1,200W rated output with up to 1,800W surge, rich mix of AC, DC, USB and wireless outputs. | Off-grid cabins or long-term forest living with routers, laptops, lights, small appliances and emergency backup needs. |

Because these stations use LiFePO₄ batteries, they’re designed for long cycle life — useful when you’re charging and discharging almost every day in a forest setting.

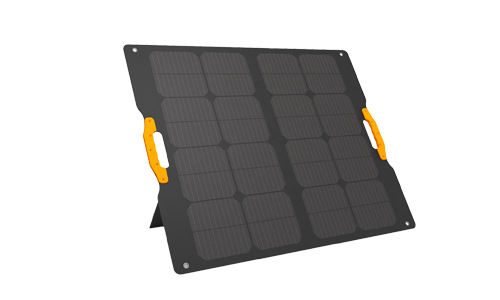

9.4 Adding solar for true off-grid power

To keep your power station topped up far from outlets, pair it with a folding solar panel. UDPOWER’s 120W portable solar panel is designed to work with their stations and packs down into a suitcase-style form factor for easy transport.

- On a sunny day, a 120W panel can put a few hundred watt-hours back into your battery — enough to recharge phones, lights and a laptop.

- Angle the panel toward the sun and move it a couple of times per day for best results.

- Always follow the included manual and avoid using panels in unsafe wind or lightning conditions.

Whether you choose UDPOWER or another brand, the main idea is the same: a compact station plus a folding panel can quietly power your “forest office” without the noise, fumes or maintenance of a gas generator.

10. Sample Daily Routine in the Woods

No two forest setups look the same, but this sample routine shows how a typical day might flow when you’re living out of a semi-permanent camp.

Morning

- Check weather forecast (if you have service) or sky conditions.

- Make breakfast, boil or filter water for the day.

- Inspect camp for damage, animal sign or fallen branches.

- Set up solar panel in full sun and plug in your power station.

Midday

- Work on projects (wood processing, shelter improvements, journaling, remote work).

- Move the solar panel as the sun moves.

- Check in with family or a trusted contact when possible.

Evening

- Cook dinner and clean up thoroughly to avoid attracting animals.

- Top off headlamps, radios and phone from the power station.

- Review the next day’s plan, weather and any resupply needs.

- Secure food and trash before bed.

11. Common Mistakes to Avoid When Living in the Woods

- Going from zero to full-time immediately. Start with shorter trips and build experience.

- Ignoring local regulations. Overstaying limits or breaking fire rules can lead to fines and closures.

- Underestimating weather. Even in summer, cold rain and wind can create dangerous conditions.

- Relying on one gadget for safety. Phones die, GPS units fail; always carry analog backups.

- Neglecting mental health. Isolation, constant work and poor sleep add up fast — plan social contact and rest days.

- Leaving a trace. Abandoned tarps, trash and “improvements” damage the land and make life harder for everyone.

12. FAQs About Living in the Woods

Is it realistic to live in the woods full-time?

It can be, but it’s closer to running a small off-grid homestead than to a long camping trip. You’ll need legal land access, a sustainable water source, a reliable power and heating setup, and a plan for medical care, income and winter conditions.

How much money do I need to start?

Costs vary wildly. At minimum, budget for quality shelter and sleep gear, clothing, food storage, power, tools, and transportation — plus emergency savings. If you’re buying land or building a cabin, treat it like a serious long-term investment, not a weekend project.

Can I rely on hunting and foraging instead of bringing food?

For most people, no. Responsible hunting and foraging require skills, local knowledge, and the right permits. It’s safer to treat them as supplements to a solid pantry, not your main food plan, especially in your first seasons.

Do I really need a power station if I want to “disconnect”?

Not necessarily, but it’s a smart safety buffer. Even if you stay off social media, having power for lights, emergency communication and navigation tools can make the difference between a manageable situation and an emergency.

What’s the best way to get started?

Take a realistic inventory of your skills, health and obligations. Then plan a short, well-equipped trip to a forest you can reach easily. Use that trip to test your gear, routine and comfort level before committing to anything longer or more remote.