How Many Amps Does a Refrigerator Use? (Running vs. Startup, With Real-World Tables)

ZacharyWilliam- Quick answer (typical amps)

- The simple math: amps = watts ÷ volts

- Where to find your fridge’s real amps

- Typical refrigerator amps by type (data table)

- Why amps spike: compressor startup + defrost

- How to measure your refrigerator amps (fast + accurate)

- Running a refrigerator on a portable power station (sizing + runtime)

- UDPOWER recommendations (kept practical, not pushy)

- Make your fridge backup last longer (easy wins)

- FAQ

- Sources (linked)

Quick answer (typical amps)

In most U.S. homes, a refrigerator runs on 120V AC. The running current (once the compressor is up and running) is often in the neighborhood of:

But here’s the part people miss: refrigerators can pull a brief startup surge when the compressor kicks on. That surge can be several times the running amps (and can also spike during auto-defrost).

Practical takeaway: If you’re sizing a battery backup / inverter / generator, you need to plan for both running amps and startup (surge) amps.

The simple math: amps = watts ÷ volts

For AC appliances in the U.S., 120 volts is the most common reference point. The quick relationship is:

Amps (A) = Watts (W) ÷ Volts (V)

- Example: 150W running load at 120V →

150 ÷ 120 = 1.25A - Example: 900W startup surge at 120V →

900 ÷ 120 = 7.5A

If you only know kWh per year from an EnergyGuide label, you can still estimate an average wattage (and average amps) — see the next section.

Where to find your fridge’s real amps (no guessing)

- Check the nameplate sticker (often inside the fridge compartment, on a side wall, or behind the kick plate). It may list amps (A), watts (W), or voltage (V).

- Check the owner’s manual / spec sheet. Many brands list “rated current” and sometimes “starting current.”

-

Use the EnergyGuide label (kWh/year) to estimate average watts:

Average watts ≈ (kWh/year × 1000) ÷ 8760

Then average amps ≈ average watts ÷ 120The U.S. Department of Energy’s Energy Saver site shows the standard approach for estimating appliance energy use using watts, hours, and kWh. (See: Energy.gov — Estimating Appliance Energy Use)

- Measure it (best method). A plug-in power meter can capture real usage over hours/days. If you use a Kill A Watt-style monitor, an extension cord can make the display easier to read for fridges/freezers (example instructions: Washington Electric Coop — Kill A Watt Instructions (PDF)).

Typical refrigerator amps by type (use this as a starting range)

The table below combines what people usually mean by “amps a refrigerator uses”: running amps (compressor on) and startup/surge amps (brief). Your actual numbers depend on size, efficiency, ambient temperature, and compressor type.

| Refrigerator Type | Typical Running Watts (compressor on) | Running Amps @ 120V | Typical Startup / Surge Watts | Startup / Surge Amps @ 120V | Typical Annual Energy (kWh/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mini fridge / compact | 50–200W | 0.4–1.7A | 200–600W | 1.7–5A | ~100–470 (varies widely) |

| Modern top-freezer (typical home) | 100–250W | 0.8–2.1A | 400–1200W | 3.3–10A | ~300–500 (often lower if high-efficiency) |

| Side-by-side / larger configurations | 120–300W | 1–2.5A | 600–1500W | 5–12.5A | ~350–700+ |

| French door / feature-heavy (ice, extra fans) | 150–350W | 1.25–2.9A | 800–1800W | 6.7–15A | ~400–800+ |

| Older “garage fridge” / inefficient unit | 150–400W | 1.25–3.3A | 900–2000W | 7.5–16.7A | Often much higher than modern (can be 35%+ more on average) |

For real product-by-product energy numbers, the ENERGY STAR refrigerator database lets you sort by annual kWh/year: ENERGY STAR Product Finder — Refrigerators.

Why amps spike: compressor startup + defrost

1) Compressor startup (inrush current)

The compressor motor can draw a brief “inrush” current at startup before it stabilizes. This is often described as Locked Rotor Amps (LRA) in motor terminology. A simple explanation of LRA and why it spikes is here: Area Cooling — Locked Rotor Amperes (LRA).

2) Auto-defrost heater (some models)

Many modern refrigerators have a defrost cycle that can add a meaningful temporary load. If defrost overlaps with compressor operation, you can see higher watts/amps than “normal running.”

3) Ice makers, fans, and door openings

Small loads add up: condenser/evaporator fans, ice maker heaters, and frequent door openings can increase both the number of compressor cycles and total daily energy use.

How to measure your refrigerator amps (fast + accurate)

Option A: Plug-in power meter (best for most homeowners)

- Plug the power meter into the wall outlet (use an extension cord if needed for readability).

- Plug your refrigerator into the meter.

- Let it run at least 24 hours to capture normal cycling and defrost behavior.

- Record: kWh (daily energy), watts (instant), and if available, amps.

Example instructions for this style of monitor: Washington Electric Coop — Kill A Watt Instructions (PDF).

Option B: Clamp meter (good for electricians / advanced users)

- Measures current on a conductor directly (not a plug-through device).

- Useful when you need to see inrush behavior at startup.

- Requires safe access and basic electrical knowledge.

What to write down

- Running amps while compressor is on

- Peak amps during startup

- kWh/day (most useful for runtime planning)

Running a refrigerator on a portable power station (sizing + runtime)

If you’re planning for outages, camping cabins, or off-grid use, focus on these three specs: (1) running watts, (2) startup surge watts, and (3) daily energy (Wh).

Step 1: Make sure the inverter can handle both running and surge

- Continuous (rated) output should exceed your fridge’s running watts.

- Surge/peak output should cover compressor startup (and any defrost spike).

Step 2: Estimate how many watt-hours you need

If you measured kWh/day on a power meter, convert it to Wh/day: Wh/day = (kWh/day × 1000).

If you only have the EnergyGuide kWh/year, you can estimate average watts: avg W ≈ (kWh/year × 1000) ÷ 8760 (method consistent with DOE’s energy estimation approach: Energy.gov).

Step 3: Convert battery capacity (Wh) into a realistic runtime

A simple planning formula is:

Runtime (hours) ≈ Battery Wh × 0.85 ÷ Average watts

The 0.85 factor is a practical “real-world” efficiency placeholder for inverter + conversion losses. For best accuracy, use your own meter data.

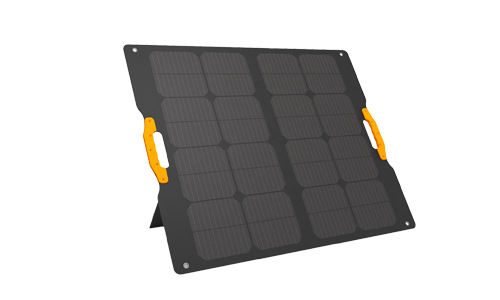

UDPOWER recommendations

Below are UDPOWER models that match common refrigerator scenarios. The key is pairing the power station’s continuous output and surge capability to your fridge, then choosing enough Wh capacity for the runtime you want.

| Use Case | Suggested UDPOWER Class | Picture | Why it fits | Specs (from UDPOWER pages) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mini fridge / compact fridge (low surge) | UDPOWER C200 or UDPOWER C400 |  |

Lightweight options for small loads; good for short outages or travel. | C200: 192Wh capacity, 200W output, surge up to 400W (see product page). C400: 256Wh capacity, 400W output, 800W surge (UD-TURBO) (see product page). |

| Portable fridge / car fridge / small home fridge (moderate surge) | UDPOWER C600 |  |

More battery capacity and higher surge headroom than small units. | 596Wh capacity, 600W rated output, peak 1200W (see product page). |

| Standard home refrigerator (typical outage backup) | UDPOWER S1200 |  |

Built for higher appliance loads; practical when you need solid surge handling. | 1,190Wh capacity, 1,200W rated output, UDTURBO up to 1,800W (see product page). UDPOWER notes it can run a standard refrigerator (60–100W) about 10–15 hours depending on real usage. |

What runtime looks like (example planning table)

These are “planning” estimates using Runtime ≈ Wh × 0.85 ÷ Avg W. Your fridge’s average watts depend heavily on duty cycle.

| Average Fridge Load (Avg W) | C400 (256Wh) | C600 (596Wh) | S1200 (1,190Wh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50W (efficient fridge cycling lightly) | ~4.4 hrs | ~10.1 hrs | ~20.2 hrs |

| 80W | ~2.7 hrs | ~6.3 hrs | ~12.6 hrs |

| 120W | ~1.8 hrs | ~4.2 hrs | ~8.4 hrs |

If your goal is “keep the fridge cold as long as possible,” measuring kWh/day with a power meter for 24–72 hours is the single best upgrade you can make to your planning.

Make your fridge backup last longer (easy wins)

- Pre-cool before an outage: turn the temperature slightly colder when severe weather is forecast.

- Keep doors closed: every door opening forces longer compressor run time.

- Use thermal mass: cold water bottles help stabilize temperature.

- Clean condenser coils: dirty coils increase energy use and runtime.

- Skip unnecessary features during backup (some ice makers/heaters add load).

Refrigerator Amp & Runtime Calculator (quick planning)

FAQ

Does a refrigerator really use only a few amps?

Many do—most of the time. The compressor doesn’t run continuously. When it’s off, the fridge draws much less. The “few amps” usually refers to compressor running amps, not the brief startup surge.

Why does my meter show higher watts sometimes?

Common causes: compressor startup (inrush), auto-defrost heater, ice maker heater, or heavy door openings increasing cycle time.

Can I estimate fridge amps from the EnergyGuide label?

Yes—at least average amps. Convert kWh/year to average watts using: (kWh/year × 1000) ÷ 8760, then divide by 120V to get average amps. For the general method of converting watts/hours to kWh, see: Energy.gov.

What’s the best way to size a backup power station for my fridge?

Measure kWh/day with a plug-in power meter (24–72 hours). Then choose a power station with enough surge output for compressor startup and enough Wh for your target runtime.

Sources (linked)

- U.S. Department of Energy (Energy Saver): Estimating Appliance and Home Electronic Energy Use

- ENERGY STAR Product Finder (refrigerators; sortable by kWh/year): ENERGY STAR Certified Refrigerators

- Example “Kill A Watt” style measurement instructions (PDF): Washington Electric Coop — Kill A Watt Instructions

- Locked Rotor Amps (LRA) explanation: Area Cooling — LRA (Locked Rotor Amperes)

- UDPOWER product specs used in this guide: S1200, C600, C400, C200